top of page

Sumerian Shakespeare

Another Standard of Ur?

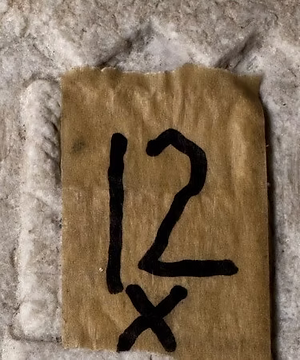

A stone plaque was recently confiscated in Bulgaria and turned over to the National Museum of Iraq. Is this stolen artifact a long lost copy of the Standard of Ur?

* * * Select a page by clicking on a link below, or use the drop-down menu on the right * * *

The Mystery Plaque Is it a treasure or a fraud?

A Stolen Artifact? Was it looted by tomb robbers?

Copied from the Standard of Ur Is it real or fake?

bottom of page